This is the second in a series of four posts discussing how a revenue integrity program can help clinical, compliance and revenue cycle teams join forces to address the increasing challenges of compliance. In our first post, we discussed how a revenue integrity program can be a unifying force in the organization.

When it comes to medicine, many like to wax poetic over the simpler times of the 1990s. Although we have improved dramatically when it comes to medical advances and quality of care over the past several decades, clinicians sometimes long for a return to certain aspects of those “good old days” when practicing medicine was a much simpler pursuit.

Looking back at the evolution of the physician practice over the past quarter century, you can certainly understand that point of view. One thing is clear: the dramatic changes affecting the health care profession since the 1990s have contributed to a growing regulatory monster, which has negatively impacted the relationship between clinicians, compliance and revenue cycle teams.

In the early 1990s the provider landscape was much less complex, consisting of private clinics and single physician practices. Doctors were paid in cash or through claims payment from insurance companies. Claims were submitted manually in a simple, straightforward process that didn’t present any confusing choices. Guidelines for documentation didn’t exist and doctors were happier because they were generating revenue and seeing multiple patients – sometimes up to 40 a day. Physicians referred to their handwritten notes to refresh their memory when the patient returned for a follow-up. The one-to-one relationship with patients was highly satisfying. In those bygone days, there was little talk of compliance issues when it came to claims or reimbursements.

Forward-thinking organizations understand that developing a revenue integrity program that unites these groups not only makes for a healthier work environment, but also enables the organization to meet its goals.

The rise of capitation

Moving into the mid 1990s, insurance companies began to question the amount of money they were paying physicians. Portraying the move as “helping patients,” third-party payers began moving to capitation – the payment of a fixed amount of money per patient per unit of time, paid in advance to the physician for the delivery of health care services.

As part of this new model, insurance companies began analyzing data to see how much effort physicians were expending for each service provided to patients. This was the genesis of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes – especially for office visits. This was also the time we first began to see specific documentation guidelines that ultimately determined what the physician would be paid.

As documentation requirements for proper billing increased, confusion ensued. Many physicians felt that the government and private payers were taking advantage of the chaotic period when physicians were adjusting to the new – often vague and confusing – process and paying them less than what they rightly deserved.

Let the auditing begin

To combat the risk of being shortchanged for services rendered, physicians became more conservative in their approach and used high-level – more expensive – codes in their documentation.

To minimize this practice, Medicare began auditing clinicians and forcing them to reimburse their fees when they felt the physician had “over coded” for a service. This system spawned ill will between the government and the AMA and other physician associations. Providers demanded more clarity around documentation rules.

In 1997, Medicare announced a new set of rules and regulations, but instead of simplifying documentation, it made things even more complex. The forms doctors were required to fill out were comprehensive and caused even more confusion.

Beginning of the end of private practices

Doctors in private practices and small clinics realized that to comply with the growing number of guidelines, they would have to hire coders to input the right information, and internal auditors to make sure the coders were submitting correct claims. As expenses mounted, profit margins plummeted – causing many physicians to abandon their private practices and flee to larger physician groups that could better sustain the increased overhead costs.

The late 1990s saw the growth of residency programs at academic medical centers (AMCs), staffed by recent graduates of those schools. These young doctors would work under the direction of more experienced attending physicians. These programs, largely funded through Medicare Part A, caused more turmoil when it came to claims submittal. Many of these AMCs misinterpreted the rules and began billing for services for both the resident and attending physician – basically double dipping – causing them to get hit with large reimbursement penalties when the government discovered the practice.

Organizations reacted to these and other penalties for non-compliance by placing more responsibility on administrators to develop policies and procedures, and to make sure clinicians were following them. Administrators met this requirement by creating compliance departments to proactively identify and report on any physician documentation errors they uncovered. Although uncomfortable for both auditors and clinicians, the process was necessary because the financial impact of paybacks and penalties could be substantial.

Backlash causes revenue hit

As compliance departments began to warn about the severe penalties that could result from over coding, many clinicians over-corrected and began using lower level – less expensive – codes to be safe. They felt this would avoid the risk of being audited or penalized, thus keeping both the organization and the government happy. Unfortunately, translating this practice across thousands of physicians resulted in a sharp decline in revenue. Compliance departments were pleased since organizations were no longer being hit with penalties, but finance teams were beginning to feel the impact of a reduced revenue stream.

Moving into the 2000s, the regulations kept coming: HIPPA privacy, Stark conflict of interest, Medicare changes to DRG reporting, ICD 9 and 10, and MACRA – all of which required more investment with no return, thus further eroding healthcare profit margins. The result: more administrators, more auditors, more cost, and less reimbursement.

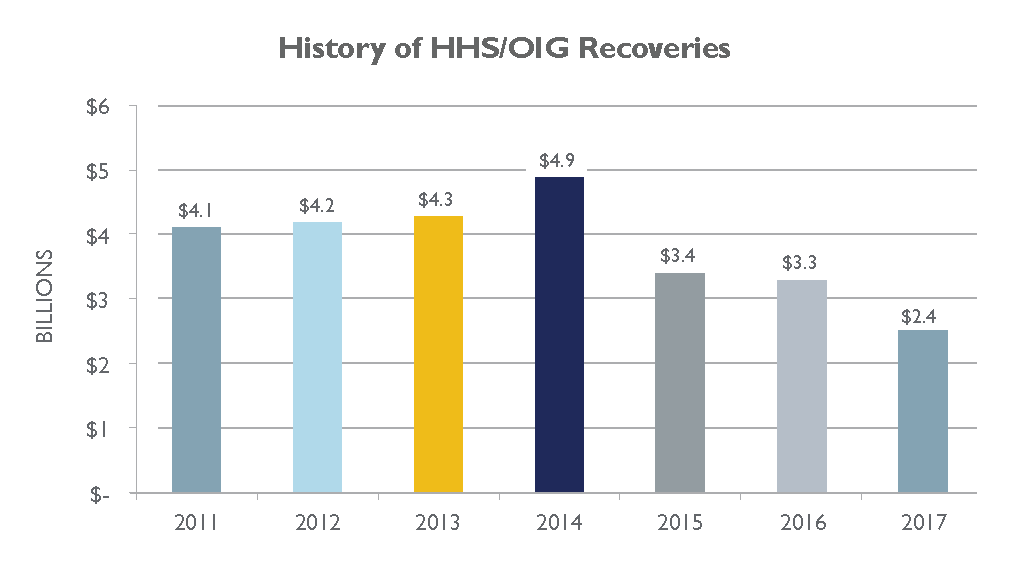

Since 2011, HHS and the OIG have recovered over $26 billion from individuals and organizations who attempted to defraud federal health programs, or who sought payments to which they weren’t entitled. 1

Weighed down by this growing burden, clinicians were now becoming less productive, able to see fewer than half the patients they had seen in the past. This reduced billings and reimbursements even further. This situation was further impacted with the widespread implementation of EMRs and the demands of Meaningful Use, putting an additional documentation burden on clinicians.

What now?

This evolution has resulted in the situation we have today: three groups – clinicians, compliance teams and revenue cycle departments – each focusing on their own areas and goals. Clinicians want to treat patients effectively; compliance teams want to make sure all the documentation and processes are being followed; and revenue cycle departments want to make sure the organization is billing and collecting every dollar to which it is entitled.

It’s easy to understand why these three groups can sometimes be at odds, however the answer is not to eye each other warily, but instead to come together to support their overall objectives: provide outstanding patient care, stay in compliance and collect all legitimate revenue. Forward-thinking organizations understand that developing a revenue integrity program that unites these groups not only makes for a healthier work environment, but also enables the organization to meet its goals.

In the third post of the series, we will further discuss how regulatory demands have strained the relationship between clinical, compliance and revenue cycle teams.

1 Source: Annual updates from the Office of the Inspector General under the Department of Health and Human Services